Details

Gharem’s personal reaction to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, have laid the foundation for much of his artistic output, however, Pause is the work most closely concerned with the destruction of the World Trade Center. For Gharem, like most of us, witnessing the collapse of the Twin Towers on television was one of those shocking moments that seems to make the earth stand still or pause. When he later found out that two of the hijackers were classmates he wondered why they had chosen that horrific path while he, who had been given the same education, elected another. This expressive “stamp painting” is Gharem’s response.

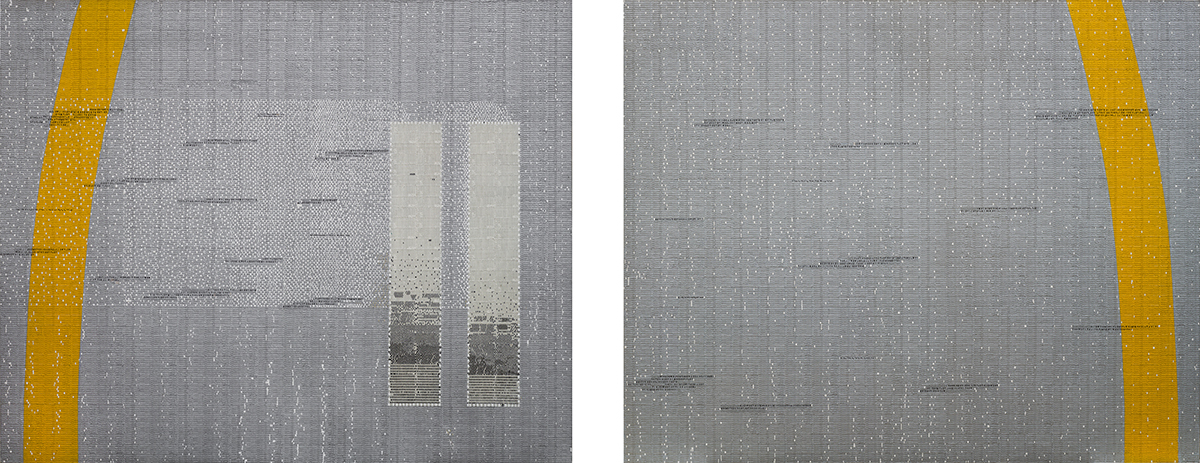

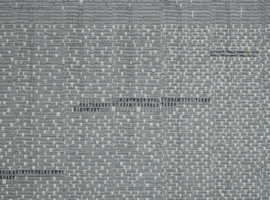

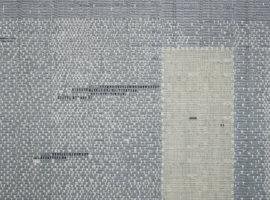

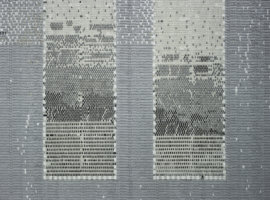

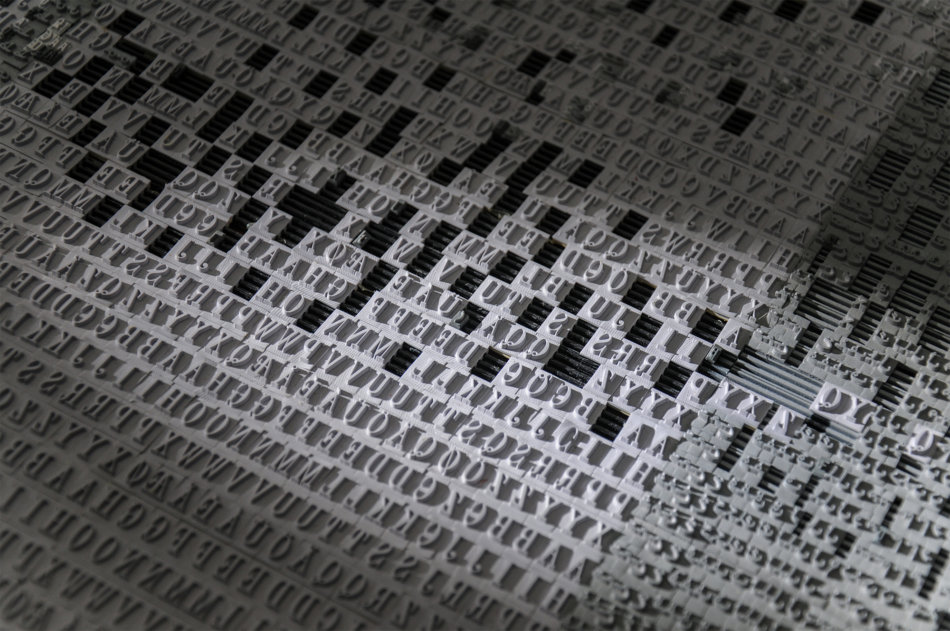

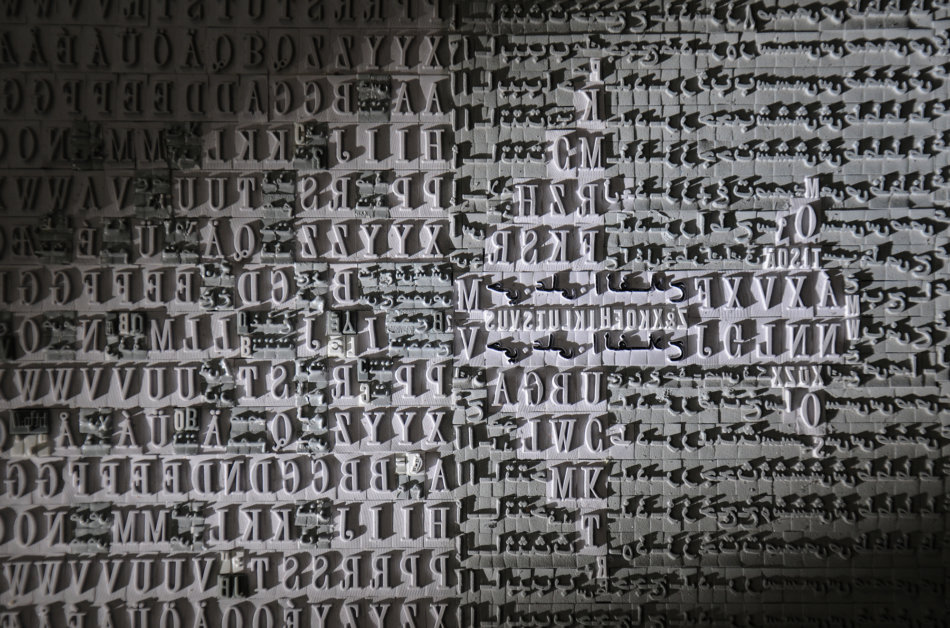

On the left panel of the diptych are two solid rectangles seemingly rendered in shades of gray but, upon closer inspection, formed of tiny rubber letter stamps in Arabic and English and painted in black and white. The pair of rectangles signifies the digital symbol for “pause” as well as the Twin Towers, which look like ghostly after-images. An incomplete yellow arch–resembling a golden rainbow—straddles the diptych and draws our eyes back to the center. To underscore the visual connection with 9/11, Gharem has embedded within the composition twenty-seven short quotations formed of stamps painted black and written in reverse. On the far, left just to the right of the golden arch, he offers these words from Sandy Dahl, wife of Flight 93 pilot Jason Dahl, “If we learn nothing else from this tragedy, we learn that life is short and there is no time for hate.”

Article by Linda Komaroff, Curator and Department Head of Art of the Middle East at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Process

About Stamp Painting

In 2008 Gharem had been made a Major in the Saudi Army. What did this mean in practical terms? A bigger salary, for one, more responsibility, and many more hours behind a desk. He had more forms to plough through, more administration to deal with, and otherwise more slips of paper to stamp.

Gharem was interested in these stamps. No matter how complex the logic that informed his decisions, these stamps reduced his thoughts to a single stab, a binary ‘stamp’ or ‘no-stamp’. Each day in Saudi Arabia thousands of stamps are slammed down onto a mosaic of official papers by bureaucrats, officials, policemen and soldiers, and together they articulate an unconscious and collective imprimatur. They spell out what is acceptable, or which is the ‘right path’.

Gharem began to buy as many children’s printing kits as he could find. In each was a small set of rubbery Arabic letters, numbers and numeric functions. Once he had amassed several hundred of these, he packed together the letters until he had two flat surfaces, each one gun-metal grey and full of undulating, bureaucratic detail.

“The feeling I had at the time was that it was impossible to change the minds of all the people against Siraat. Together they formed a wall. A system. The system did not have a human face, but it had created a stamp of disapproval. It can be very hard to defend yourself against this.”

Onto one of the two rubbery beds destined for London, as well as the yellow stripe of the road in Siraat, Gharem painted a pair of dark rectangles using industrial lacquer paint. Near the top of one he added what looked like an arrow or a plane.

His desire to set up a workshop points to another aspect of Gharem’s character. He works well in a team, especially if he is in charge. This is a man who has spent most of his life at the head of a group, whether his siblings, an army platoon, a workshop, or the team of friends he might work with on artistic projects such as Siraat.