About Stamp Painting

In 2008 Gharem had been made a Major in the Saudi Army. What did this mean in practical terms? A bigger salary, for one, more responsibility, and many more hours behind a desk. He had more forms to plough through, more administration to deal with, and otherwise more slips of paper to stamp.

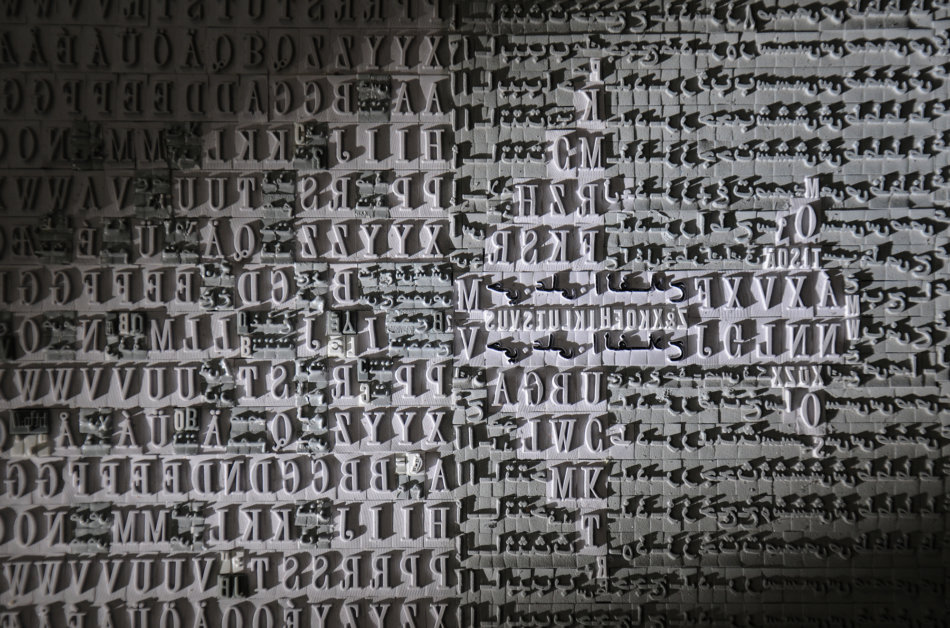

Gharem was interested in these stamps. No matter how complex the logic that informed his decisions, these stamps reduced his thoughts to a single stab, a binary ‘stamp’ or ‘no-stamp’. Each day in Saudi Arabia thousands of stamps are slammed down onto a mosaic of official papers by bureaucrats, officials, policemen and soldiers, and together they articulate an unconscious and collective imprimatur. They spell out what is acceptable, or which is the ‘right path’.

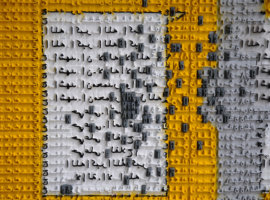

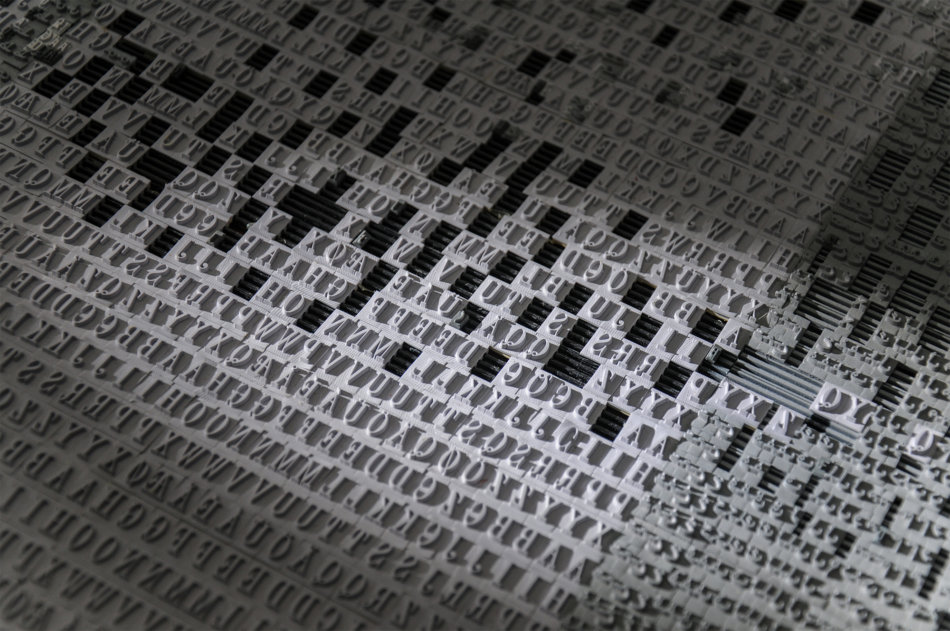

Gharem began to buy as many children’s printing kits as he could find. In each was a small set of rubbery Arabic letters, numbers and numeric functions. Once he had amassed several hundred of these, he packed together the letters until he had two flat surfaces, each one gun-metal grey and full of undulating, bureaucratic detail.

“The feeling I had at the time was that it was impossible to change the minds of all the people against Siraat. Together they formed a wall. A system. The system did not have a human face, but it had created a stamp of disapproval. It can be very hard to defend yourself against this.”

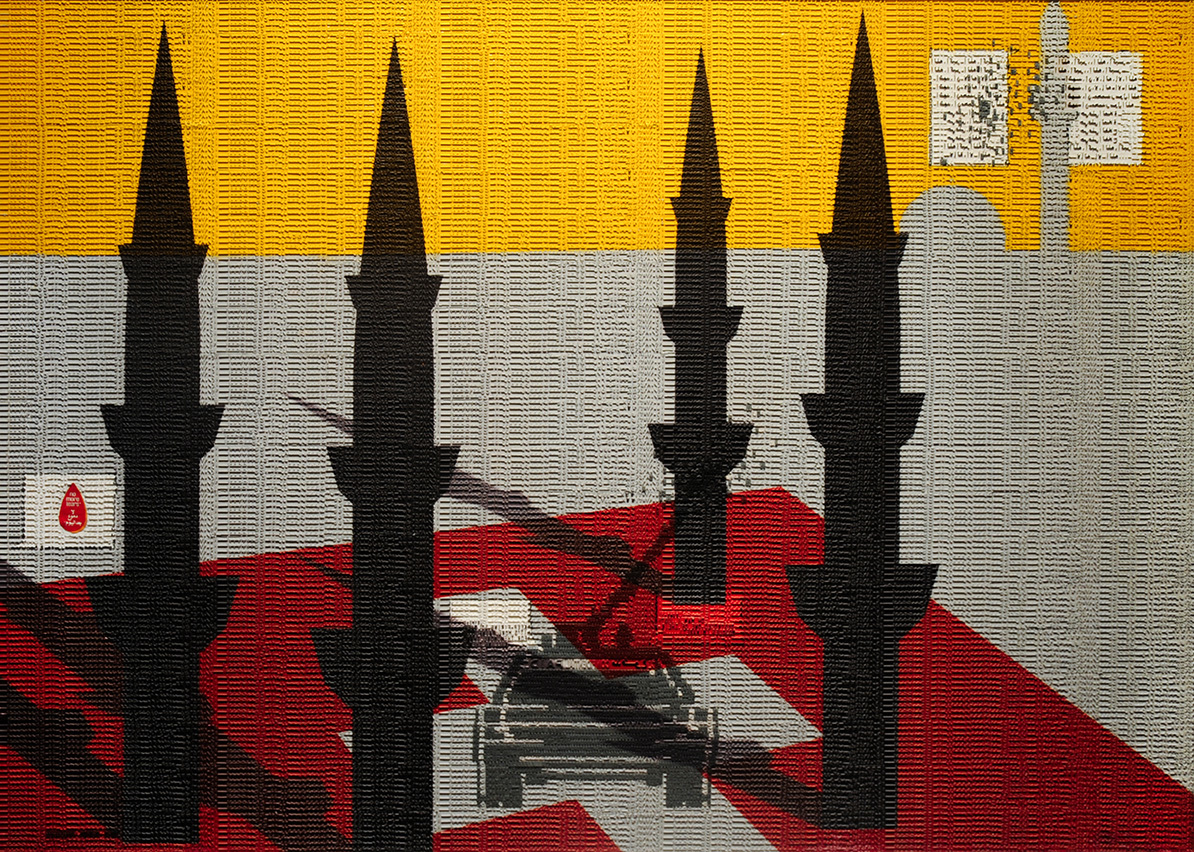

Onto one of the two rubbery beds destined for London, as well as the yellow stripe of the road in Siraat, Gharem painted a pair of dark rectangles using industrial lacquer paint. Near the top of one he added what looked like an arrow or a plane.

His desire to set up a workshop points to another aspect of Gharem’s character. He works well in a team, especially if he is in charge. This is a man who has spent most of his life at the head of a group, whether his siblings, an army platoon, a workshop, or the team of friends he might work with on artistic projects such as Siraat.